Case 5.1 Organizational transformation at Nestlé[i]

Swiss-based Nestlé S. A., the world’s largest food manufacturing company, employs around 270,000 people and has factories or operations in practically every country in the world.[ii] However, Nestlé does not focus simply on building and exploiting global brands. As noted by former CEO Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, “There is a trade-off between efficiency and effectiveness in global brands .. . Operational efficiency comes from our strategic umbrella brands. But we believe there is no such thing as a global consumer, especially in a sector as psychologically and culturally loaded as food.”[iii] Although Nestlé does not believe in homogeneous consumer preferences, it has started to integrate its businesses at the regional level and even the global level – it has become much more than a holder of a portfolio of national units.

The inherited unique features at Nestle´

During his tenure as CEO from 1997 to 2008, Peter Brabeck-Letmathe as well as his predecessor Helmut Maucher, identified two unique features at Nestlé that should not change: first, the commitment to decentralization to cater to local tastes, and second, the minor role of information technology in everyday operations, relative to the importance of its employees, brands and products. At that time, Nestlé operated more like a holding company, with country-by-country responsibility for many functions.

Such an organization certainly helped Nestlé on the marketing side. Local managers could change the product taste, formulation and packaging according to local preferences. For example, Nescafé, Nestlé’s instant coffee brand, had 200 different variants: in Russia, Nescafé was very thick, strong and sweet, totally different from the bitter flavour in Western Europe. In Britain, Kit Kat consisted of chocolate and wafers, but in Japan, Kit Kat had a lemon cheesecake flavour.[iv]

However, such a decentralized organization leads to efficiency losses. Until the mid-1990s, 42 Nestlé factories located in the US still purchased their raw materials separately. As a result, a single supplier charged different Nestlé factories more than 20 different prices for vanilla. Moreover, the downplaying of information communication technology (ICT) aggravated the inefficiencies. For example, even though senior managers at Nestlé USA knew about the existence of different prices for vanilla, they had difficulty finding out which factories were over-charged, as each factory used a different purchasing code for vanilla.

Consolidating the business

As Nestlé expanded, competitive environments forced it to become more efficient. In spite of its status as the largest food manufacturing company in the world, its profit margins were lower than those of its main competitors, such as Unilever, Heinz and Danone. Starting in the late 1990s, Nestlé embarked upon a fundamental transformation of its business organization. It shifted away from its longstanding geographic/functional focus to incorporate some product-oriented organization. The geographic focus still dominates, however.

A decentralized front end (markets and businesses)

Nestlé currently operates its downstream activities with three geographic zones and seven strategic business units (SBUs). Zone organizations refer to the major regions – Zone Europe, Middle East and North Africa, Zone Americas and Zone Asia, Oceania and Sub-Saharan Africa, with zone executive officers responsible for market/region business targets[v]. The seven SBUs (Powdered and Liquid Beverages; Water, Milk products and Ice cream, Nutrition and Health Science; Prepared dishes and cooking aids; Confectionery; and PetCare;)[vi] develop business strategies for selected market clusters, accelerate innovation and renewal, and introduce ‘brand boards’ to develop strategic brands.

To achieve focus in its branding, Nestlé operates with international umbrella brands, such as: Nestlé, Purina PetCare, Maggi, Nescafé, Nespresso, Nestea, San Pelegrino, Perrier, and Buitoni. However, strong local brands are still kept, such as the Golden Morn cereal brand in Nigeria and the Rolo brand in the UK. Moreover, the regional market head is responsible for the SBUs, and the country market head is responsible for the market/country performance. The country market head also functions as a business portfolio strategist in a given market. In this way, the former decentralized structure is still kept alive for many downstream activities.

In some countries, including many African countries, Nestlé still remains completely decentralized, with powerful country managers responsible for the operations in their host countries, as local features remain particularly idiosyncratic there.

A regionally or globally run backline (factories and shared services)

To be cost-efficient, Nestlé has streamlined its upstream/back office activities by integrating the management of its factories into regional and even global management units. For example, in four and a half years between the end of 1998 and mid-2003, Zone Europe, Middle East and North Africa closed or sold 68 factories, reducing the number of factories in Europe from 179 to 140 even after acquiring 29 factories during the period. The reduction in number of plants reflects the rationalization efforts at the back end of the value chain, in order to gain scale economies and better international coordination. Similarly, in New Zealand, Australia and the Pacific Islands, Nestlé integrated the functions of accounting, administration, sales and payroll.

Moreover, Regionally Shared Service Centres have also been established, to provide back-office functions for each region. For example, in the Americas Zone, Nestlé Business Services provides the purchasing, HR/payroll, retail sales execution, disbursement, general accounting, operations accounting, ICT maintenance, transportation, tax and legal services for all the operating companies in the region.

Finally, the three geographic units have started to implement regional ICT systems and common standards. For example, the three geographic units had been using different inventory, accounting and planning software; in 2001, Nestlé introduced a single company-wide resource planning system called ‘GLOBE’ (Global Business Excellence), in order to standardize companywide ICT systems and to leverage scale economies in its back-end activities.

Results of the GLOBE project

The initiation of the GLOBE project in 2001 reflected a strong movement by Nestlé to improve on its apparent inefficiencies in operational and financial practices. Implementing a companywide SAP system required tremendous efforts, and though senior management initially faced resistance from employees, the system promised significant benefits.

By 2010, the GLOBE project had been implemented in over 90 countries, providing Nestlé with global data standards, a common IT platform, and improved operations.[vii] Implementing data standards allowed Nestlé to consolidate data from all of its subsidiaries across each geographic region and to transfer information readily between counterparts in transactions. Strategic decisions could be made faster and with greater confidence as information could be gathered in minutes instead of days. The common IT platform allowed Nestlé to reduce the volume of data used by 65 per cent from 2006 to 2010.[viii] In addition, Nestlé was able to leverage better its scale by consolidating purchases with suppliers across its multiple product lines, saving billions of dollars in the process[ix].

Ultimately, the GLOBE project helped Nestlé to identify areas within its value chain where inefficiencies were present. This organizational re-engineering at Nestlé allowed the firm to become better positioned for future acquisitions, as part of its international expansion strategy.[x]

From GLOBE to ‘Nestlé Business Excellence’ to ‘ServiceNow’

Building on the solid IT infrastructure implemented and shaped by the GLOBE project, Nestlé decided in 2014 to create the new Executive Board function “Nestlé Business Excellence”, which combines Nestlé’s corporate support functions GLOBE and Nestlé Business Services as well as its corporate initiative Nestlé Continuous Excellence. The goal of this new Executive Board Function is to bring speed and agility to all support functions.[xi] As explained by Paul Bulcke, Nestlé’s CEO at that time (from 2008 to 2016): “While always privileging a decentralized structure to stay close to the local consumer and keep agility in execution, we are increasing our efforts to better leverage our scale. We are looking into how our company is organized and operates to keep an optimal balance between category and geographic focus. By taking these steps, we are building our company for continued growth and performance.”[xii]

As Nestlé is continuously looking to further improve its ICT infrastructure, it implemented the so-called “ServiceNow” platform in 2020, combining more than 25 applications in one system. Gian Paolo Perrucci, Senior Platform Group Manager Common Tools & Services at Nestlé, notes, “We had a [ICT] landscape that was very fragmented and we wanted to have one single platform where everything would sit on top. And we chose ServiceNow with an ambition to provide a better user experience to our users and more efficient ways of working to our IT workforce”[xiii]. The ServiceNow platform allows product managers to implement an app as relevant to their needs, thus giving them autonomy. At the same time, the platform is shared across the organization and consequently provides a common strategic direction.

Grouping markets into clusters

Inside each SBU, Nestlé groups its markets into clusters, not by region but by other similarities, such as consumer preferences or the stage of market development. For example, in its coffee business, Nestlé has defined two clusters, according to consumers’ coffee drinking habits. The first cluster, where soluble coffee is the norm, includes the UK, Japan and Australia; the second cluster consists of the USA, Germany, France and Spain, which are only emerging markets for soluble coffee. In those markets, roast and ground coffee are dominant. Similarly, Nestlé groups its confectionery markets into four different clusters based on consumers’ eating habits.

Managers within the same cluster can develop strategies together, share best practices and innovations, and achieve synergies in manufacturing and some marketing services. Managers also transfer knowledge across clusters, although that is less common.

Moving away from the independent subsidiary model

Nestlé is transferring knowledge more between subsidiaries. For example, Nestlé Purina PetCare was the market leader in the US in 2004, with a 31 per cent market share of total pet food sales. However, in Europe, Nestlé Purina PetCare had only 24.5 per cent in 2004, well behind the 40.1 per cent market share of Mars, the market leader. To catch up, managers started to apply in Europe several concepts that had worked in the US, such as the ‘small serving’ concept. In the mid-1990s, US consumers still bought primarily multi-serve cans for their pets. In recent years, however, small serving cans (e.g., cans containing only a single serving) gradually became more popular. Accordingly, Nestlé Purina PetCare North America developed a very profitable small serving can called Fancy Feast. Nestlé Purina PetCare then introduced small serving cans in Europe, which helped it to narrow its market share gap with Mars.

In Europe, managerial attention in the past had usually not focused on the entire region, but unfortunately on only some of the national markets, thereby missing significant business opportunities. For example, the efforts of European PetCare focused on France and the UK, the top two markets in Europe, but not Germany, the number three European market. In Germany, Nestlé PetCare employed a specialist strategy by focusing on premium, high-end products. As explained by John Harris, the head of European PetCare, “We as a company have never been strong in Germany, we’ve never focused a lot of resources in Germany and it’s not in our strategic plan to become a dominant player in Germany. In Germany we want to be a player but we are not willing to invest what is required to be the number one player.”[xiv]

In 2004 and 2005, then-CEO Peter Brabeck-Letmathe stressed the need for substantial changes in organizational functioning at Nestlé, including a stronger business focus by delegating profit responsibilities to business executive managers or divisional managers and establishing regionally/globally shared services (see Figure 5.7 for the organizational structure in 2012).[xv]

‘Nestlé on the Move’

In 2002, after Nestlé started consolidating its decentralized management processes, it found that its organizational functioning included numerous dysfunctional incentives and systems. It placed value on seniority rather than skill; created loyalty to direct managers rather than to the organization; and fostered internal competition rather than value creation.[xvi]

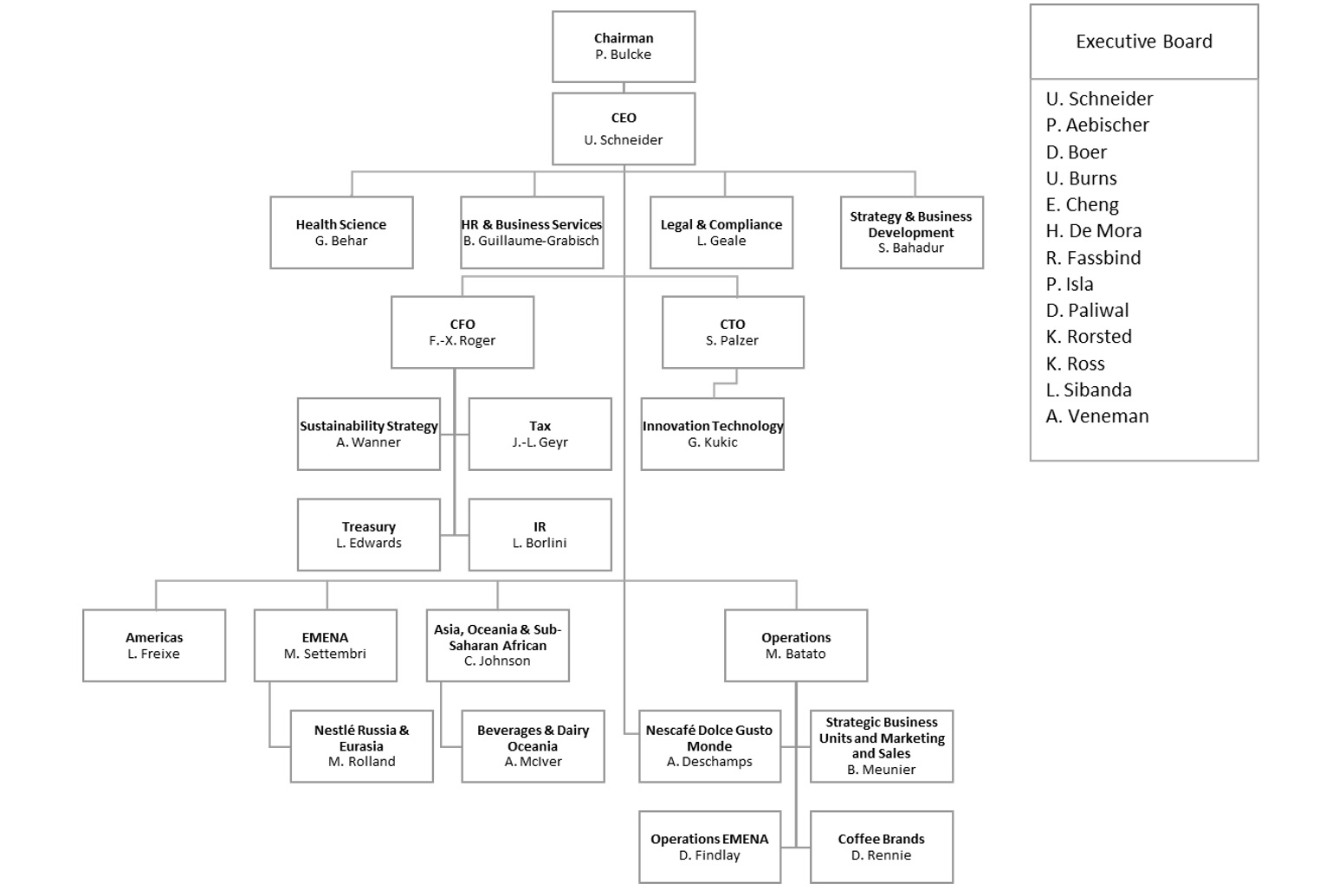

Figure 5.7

Organizational structure at Nestlé in 2012

Nestlé realized that if it wanted to properly execute its long-term strategy it would need to change its modus operandi. Over a period of several years, a change process called ‘Nestlé on the Move’, shifted the company from a hierarchical structure to a network structure consisting of network ‘hubs’.[xvii] This horizontal approach allowed the company to become more flexible by making departments more autonomous when trying to meet business targets. Hierarchical levels within factories, for example, were decreased from an average of five to seven levels to just three or four.[xviii] The decrease in vertical levels reduced the probability of promotion; however, Nestlé decided to place greater emphasis on moving employees across different regions and functions.

Nestlé’s strategic direction also evolved to focus more on becoming a leader in nutrition, health and wellness. In 2007, the company announced that the role of CEO and Chairman would be separated. Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, continued his role as Chairman until his retirement in 2017, having served as the Chairman for twelve years and Paul Bulcke accepted the new role of CEO. Paul Bulcke had achieved great success as head of Zone Americas and his younger age provided reassurance that Nestlé would be forward looking, building upon his strategic leadership.[xix] Bulcke remained in the CEO position for eight years, until he in turn was appointed as the Chairman in 2017, again following in Brabeck-Letmathe’s footsteps[xx]. Under Bulcke’s leadership, the company continued its journey on becoming the leading Nutrition, Health and Wellness Company.

Furthermore, Ulf Schneider was appointed CEO in 2017, succeeding Paul Bulcke. In contrast to his predecessors, Schneider was an ‘outsider’, joining Nestlé from the German health and medical care company Fresenius Group[xxi].

The affirmation of the Nutrition, Health and Wellness strategy

First introduced as Nestlé’s strategic vision to become a leading nutrition, health and wellness company in the late 1990s, Nestlé renewed this vision in 2018, when it announced the implementation of the accelerated long-term, value creating, Nutrition, Health and Wellness (NHW) strategy, sharpening its focus on food, beverage and nutritional health products [xxii]. Furthermore, by enhancing its focus, Nestlé seeks to deepen resource commitment to its key growth initiatives and facilitate the implementation of its accelerated long-term value creation strategy[xxiii].

This review and confirmation of the NHW strategy comes after Nestlé continued to struggle in terms of net income margins, despite having significantly higher gross income margins than those of its main competitor, namely Kraft. It also follows the inception of the new SBU for Nutrition and the re-structuring of the infant nutrition business, moving from a globally managed to a regionally managed business in 2017[xxiv]. Nestlé’s re-organization of its ICT setup in 2018 marked another decision that enhanced Nestlé’s operational effectiveness[xxv].

Further decisions from 2019, in line with its NHW strategy, are the sale of Nestlé Skin Health[xxvi] as well as the inception of the new SBU Waters, which succeeds Nestlé Waters business and is now integrated into the three geographical Zones (see Figure 5.8 for the organizational structure in 2021). The re-structuring of the water business means changing it from a stand-alone, globally managed business with headquarters in France, to one managed locally in the company’s various regions[xxvii], once again affirming Nestlé’s commitment to decentralization and to cater to local tastes.

Figure 5.8

Organizational structure at Nestlé in 2021[xxviii]

QUESTIONS:

- What was Nestlé’s initial organizational approach as an MNE (centralized exporter, international projector, international coordinator or multicentred MNE)?

- Has Nestlé transformed itself towards a less homogeneous, more multidimensional model? Can you identify certain Nestlé subsidiaries with specific roles – e.g., strategic leaders or contributors?

- Has Nestlé been able to transfer knowledge from ‘strategic leader’ subsidiaries to other types of subsidiaries? Please identify an example in the case.

- What is different between the subsidiary network discussed in this case and the model in the paper by Bartlett and Ghoshal?

- Can you provide an update on Nestlé’s international organizational approach, using materials available on the Web?

Notes:

[i] Information from Nestlé company information and Carol Matlack, ‘Nestlé is starting to slim down at last but can the world’s No. 1 food colossus fatten up its profits as it slashes costs?’, Business Week (2003), 56.

[ii] CNN, ‘Global 500’, (2011) and Derek du Preez, ‘Recipe for success – scaling ServiceNow globally at Nestlé’, diginomica, May 14, 2021, https://diginomica.com/recipe-success-scaling-servicenow-globally-nestle?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+diginomica2+(diginomica).

[iii] Alex Benady and Haig Simonian, ‘Nestlé’s new flavour of strategy: global selling: the world’s largest food company has put marketing at the heart of its plans for future growth, says Alex Benady’, Financial Times (2005), 13.

[iv] ‘Daring, defying, to grow – Nestlé’, The Economist 372 (2004), 64.

[v] Nestlé S.A., Half-Year Report January – June 2021, 2021.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] ‘2010 Half year results roadshow transcript’, Nestlé press release. www.nestle.com/ Common/NestleDocuments/Documents/Library/Presentations/Sales_and_Results/ 2010_HYResults_Roadshow_Transcript.pdf (11 August 2010).

[viii] Deborah Ball, ‘After buying binge, Nestlé goes on a diet; departing CEO slashes slow sellers, brands; “no” to low-carb Rolo’, Wall Street Journal (23 July 2007). A.1.

[ix] Rudy Puryear, Bhanu Singh and Stephen Phillips, ‘How to be everywhere at once’, Supply Chain Management Review (1 May 2007). 11.

[x] Deborah Ball, ‘After buying binge, Nestlé goes on a diet; departing CEO slashes slow sellers, brands; “no” to low-carb Rolo’, Wall Street Journal (23 July 2007). A.1.

[xi] ‘Decisions of the Nestlé Board of Directors: Creation of a new Executive Board function and redefinition of Zones Europe and AOA’, Nestlé press release. https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/new-executive-board-function-redefinition-zones (26 September 2014)

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Derek du Preez, ‘Recipe for success – scaling ServiceNow globally at Nestlé’, diginomica, May 14, 2021, https://diginomica.com/recipe-success-scaling-servicenow-globally-nestle?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+diginomica2+(diginomica).

[xiv] Nestlé company information, 2006.

[xv] Peter Brabeck, ‘Business focus and the organization’, Nestlé Investor Seminar, www.ir. nestle.com/NR/rdonlyres/264B68C6-072A-46BE-9E60-69E22C82E0F1/0/ PBL_presentation. pdf (15–16 June 2004).

[xvi] Robert Hooijberg, ‘Breaking out of the pyramid’, IMD International (June 2007).

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Robert Hooijberg, James G. Hunt, John Antonakis, Kimbery B. Boal, Nancy Lane Elsevier, ‘Nestlé on the move’, Perspectives for Managers 156 (April 2008).

[xix] ‘Nestlé Board designated Paul Bulcke as future CEO’, Nestlé press release. www.nestle.com/ Media/PressReleases/Pages/AllPressRelease.aspx?PageId=171&PageName=AllArchived PressReleases.aspx (20 September 2007).

[xx] ‘Nestlé Board of Directors and Executive Board’, Nestlé press release, https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/management-changes (27 June 2016)

[xxi] ‘Nestlé Board of Directors and Executive Board’, Nestlé press release, https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/management-changes (27 June 2016)

[xxii] ‘Nestlé Outlines Value Creation Progress’, Nestlé press release. https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/nestle-value-creation-update-july-2018 (02 July 2018)

[xxiii] ‘Nestlé to sharpen its Nutrition, Health and Wellness strategic focus, will explore strategic options for Nestlé Skin Health’, Nestlé press release. https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/nestle-explores-strategic-options-nestle-skin-health (20 September 2018)

[xxiv] ‘Nestlé reorganizes infant nutrition business, announces changes to Executive Board’, Nestlé press release. https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/infant-nutrition-business-management-changes (15 November 2017).

[xxv] ‘Nestlé Announces Re-Organization of its Global Information Technology Activities’, Nestlé press release, https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/nestle-reorganization-global-information-technology-activities (29 May 2019).

[xxvi] ‘Nestlé closes the sale of Nestlé Skin Health’, Nestlé press release, https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/nestle-closes-sale-nestle-skin-health (02 October 2019)

[xxvii] ‘Nestlé announces changes to its waters business, establishes Group Strategy and Business Development function’, Nestlé press release, https://www.nestle.com/media/pressreleases/allpressreleases/waters-business-group-strategy-business-development (17 October 2019)

[xxviii] ‘Nestlé – The organizational chart displays its 37 executives, including Ulf Schneider and Paul Bulcke’, TheOfficialBoard, https://www.theofficialboard.com/org-chart/nestle#1408584 (22 June 2021)