Porsche’s concern about operating exposure arising from changes in the exchange rate of the dollar can be traced back to heavy financial losses incurred in 1992–3. In one year, Porsche’s global sales dropped by 38 per cent to 14,000 units; in the US, its largest market, Porsche sold less than 4,000 units. The large losses were attributed not only to the global recession in the early 1990s, but also to the weak US dollar.

Founded in 1931 by Ferdinand Porsche, Porsche is a legendary German manufacturer of luxury sports cars. In 1972, Ferry Porsche and Louise Piëch, the two children of Ferdinand Porsche, changed the firm’s legal form from a limited partnership to a private limited company (German AG). An executive board and a supervisory board were set up, with executives from outside the Porsche family on the former and members mainly from the Porsche family on the latter.

The Porsche family members didn’t get along very well with their appointed chief executives in the 1980s. The feuding between the family and the executives ended only in the early 1990s when financial losses hit the company. In 1993, the family brought in Wendelin Wiedeking to head the company. Wiedeking largely remade the company by improving its efficiency and launching new products. However, the financial losses, partly resulting from exposure to the dollar, are a lingering and lasting memory, and Porsche has been watching its foreign exchange exposure very carefully since that time, implementing various exposure management strategies.[ii]

Porsche’s sourcing structure

Porsche manufactures cars in only two countries: Germany and Finland. Manufacturing in Finland occurs under a licensing agreement with Finland’s Valmet Automotive Inc. With plants in only two countries – both Euro-denominated – Porsche does not have much room to adjust its cost structure when the euro fluctuates vis-à-vis other currencies, as most of its costs are incurred in euros. However, Porsche owners and senior managers believe that the brand name stands for ‘Made in Germany’, and reflects core capabilities in engineering and manufacturing. The firm has no plan to build production plants beyond its current European facilities.

Porsche’s rivals, by contrast, have attempted to engage in ‘natural’ hedging (i.e., having revenues in the same currency as expenses). For example: since 1995, the major Japanese automakers have vastly increased their overseas production. In 2005, Japanese automakers produced for the first time more vehicles abroad than at home, with 10.93 million vehicles made at their overseas factories and 10.89 million vehicles produced in Japan. Moreover, production by these Japanese companies had become very dispersed across major regions, with “4.08 million vehicles made in the United States, 3.96 million in Asia, 1.55 million in Europe, 645,000 in Latin America, 226,000 in Africa, 135,000 in

Australia and 10,500 in the Middle East”.[iii] Like the Japanese automakers, Ford and GM have also expanded their overseas production into Asia and Latin America.

Even when compared only with other European automakers, Porsche still faces a higher operating exposure. BMW opened its first plant in South Carolina in the US in 1994, and has plans to double its US-based capacity. Mercedes plans to expand its Alabama manufacturing facility. Volkswagen, though having closed its US plant in 1988, believes that it will be able to hedge its US dollar exposure through its operating base in Brazil.

Most importantly, when compared with other European automakers, Porsche has the largest discrepancy between the location of production and the location of markets. In 2011, sales in the United States accounted for 25 per cent of Porsche’s total car sales, with no cars produced in this region.[iv] In contrast, in 2011, the US market accounted for 18 per cent of BMW’s car sales and 19 per cent of its production[v]; and 18 per cent of Mercedes’ car sales and 12 per cent of its production[vi].

Besides factory location, sourcing strategy is another way to naturally hedge against operating exposure. For example, BMW has not only set up plants in the US, but has also used it as a base for procuring parts and materials for its German-made vehicles. Although these parts and materials incur transportation costs, they have still been cheaper than equivalent domestic purchases in Germany or in other European countries, taking into account the exchange rate and lower production costs. By incurring costs in North America, BMW has created ‘natural’ hedges against operating exposure, though “BMW says that its decisions on where it locates production are driven by market needs, not currency considerations.”[vii]

In short, Porsche’s rivals are better positioned on the input market side to handle unexpected exchange-rate fluctuations.

Porsche’s exchange rate pass-through capability

Porsche’s ability to pass through to US consumers at least part of the cost of exchange-rate fluctuation varies according to the product type. Porsche’s portfolio includes three vehicle platforms: the 911 series, the Boxster and the Cayenne.

The 911 series is a premier luxury sports car. To some extent it is the only player in its own market segment. Although its sales have gone up and down, demand has been largely price inelastic, as the series has commanded high prices from the outset, and demand has depended mainly upon the potential buyers’ disposable income. In the US, Porsche could probably increase prices of the 911 series to a certain extent, in the context of exchange rate pass through, without experiencing a decrease in sales volume.

The Boxster roadster was introduced in 1996 to compete in the lower price end of the sports car market. It is priced substantially lower than the 911 series. However, this market segment is also very price sensitive and competitive, with several alternatives such as the BMW Z3 and Z4. Therefore, any increase in the Boxster’s price resulting from exchange rate pass through would probably hurt its sales.

The Cayenne is an off-road sports utility vehicle (SUV) priced at the top end of this market segment. Although the Cayenne has been a huge success, especially in the SUV-crazed American market, Porsche quickly introduced a lower-priced version as it was afraid that the high-end market segment was not a growth market. The Cayenne has since become Porsche’s most successful model, with sales of 59,873 units in 2011.[viii]

In a 2011 Automotive Performance, Execution and Layout (APEAL) study, Porsche’s 911 and Cayenne models were identified as the best cars in their segments.[ix] The APEAL study surveys 73,000 new vehicle buyers annually, and aggregates data across categories such as design, handling and comfort.[x] The popular success of these models allows for some pricing flexibility.

Overall, Porsche’s portfolio allows some exchange rate pass through. However, if the Euro appreciated strongly against the US dollar, Porsche would not be able to pass on to North American customers the full price change required without a significant reduction in sales. If Porsche wanted to avoid a significant reduction in sales, it would have to reduce its profit margins on sales in the US.

Porsche’s exposure management strategy

Instead of natural hedges, Porsche uses other strategies to manage its exposure. The first major strategy at Porsche is to compete not on price but on quality. Unlike its rivals, Porsche does not offer price rebates or discounts.[xi]

The second major strategy is an aggressive ‘put options’ hedging strategy, introduced in 2001, when the Euro bottomed out against the US dollar. With around 40 per cent of total sales in North America, Porsche feared the potential damage of a strengthening Euro in the medium term. To minimize this potential damage, Porsche purchased a set of put options, which allowed Porsche to exchange at will its US dollars from sales in the US into euros, at pre-specified exchange rates. This hedging has been so aggressive that the firm’s 2011 and 2012 sales have been hedged for 100 per cent. Porsche is typically able to cover every current and upcoming year at 100 per cent. Unfortunately, this medium-term strategy has required Porsche to forecast sales and future exposures, and it has also become very costly due to the option premiums associated with such a large options portfolio. Porsche has had to estimate sales into 2016 to hedge against the US dollar. Porsche continues to mitigate its foreign exchange exposure by means of hedging against ten different currencies. Residual risk is mitigated through forwards, simple options and more complicated structured products. The company even experimented with options on top of options on top of options to give ‘flexibility’. Goldman Sachs has estimated that Porsche currency hedging techniques manage to generate roughly €250 million a year.[xii]

However, Porsche’s hedging strategy has been criticized for being a ‘second-best solution’. As noted by Citigroup Smith Barney, “Porsche has the heaviest US exposure (and this is increasing), yet it has the lowest level of natural hedging in the sector.”[xiii]

Foreign exchange exposure in China is also increasing as Porsche aims to expand its market share in China. During the past few years, the Chinese automotive market has experienced substantial growth and is now the largest market in the world. The demand for premium cars is also rising with expected growth in 2012 reaching 15–20 per cent.[xiv] For Porsche, the Chinese market is now its second largest behind the United States. The company is responding with plans to expand from 41 dealerships in 2011, to 60 by the end of 2012.[xv] Porsche is continuing to pay close attention to the fluctuations of the Chinese currency to hedge against the foreign currency exposure.

Former CEO Wiedeking was confident about Porsche’s future profitability: “In the long term, we will have to live with an adverse dollar. There is no way out. We have to have a strategic answer for currency fluctuations .. . Our currency hedging strategy had one single purpose: we buy time to prepare ourselves for the situation when the currencies run against us.”[xvi] Porsche has started to engage in a cost-cutting programme. Industry analysts view such an approach as feasible if Porsche can reduce its cost by 2–3 per cent on the input side.[xvii]

Structural changes in Porsche

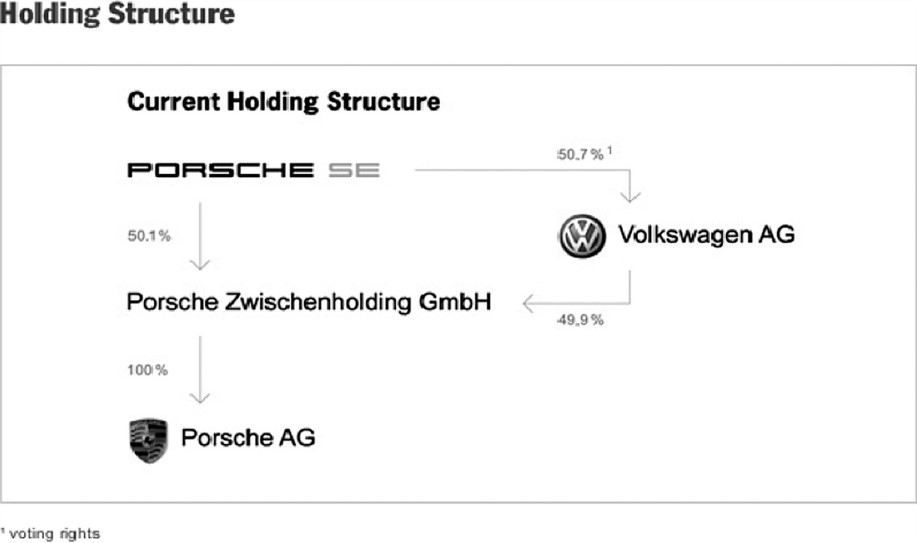

At the annual general meeting in 2007, Porsche, legally operating as Porsche AG, established Porsche Automobil Holding SE (Porsche SE), to be the umbrella holding company for Porsche. Shareholders voted in favour of establishing the holding company to manage Porsche’s equity investment and to legally register as a ‘Societas Europaea’, a term that refers to a European Public Limited Liability Company. Porsche SE would own Porsche Zwischenholding GmbH, a holding company that in turn has a 100 per cent stake in Porsche AG, its automotive manufacturing arm (see Figure 8.7)

Volkswagen takeover

Porsche’s and Volkswagen’s joint history dates back to the 1930s, when Ferdinand Porsche designed the Volkswagen Beetle. He later established his own company, namely Porsche, but the ties between the two companies continue to exist today. Executives overlap between Porsche and Volkswagen as Martin Winterkorn is the CEO of both Volkswagen and Porsche SE. In addition, Ferdinand Piëch, the grandson of Ferdinand Porsche, is the chairman of the supervisory board of the Volkswagen Group. Throughout the years, the two companies have often worked together to integrate their operations by sharing factories and even car parts. Porsche’s bestselling Cayenne model shares platform components with the VW Touareg and the Audi Q7.[xviii]

Figure 8.7

The current Porsche holding structure

It came as no surprise to the public when in the mid 2000s Porsche started to increase its ownership in Volkswagen.

In October 2008, Porsche SE shocked the markets by revealing it had control over 74 per cent of the shares in Volkswagen. The move had signified that Porsche was in the process of attempting a takeover of a company fourteen times its size.[xix] The announcement drastically drove up the share price of Volkswagen, so much so that at one point it was the most valuable company in the world. Conversely, some hedge funds lost an estimated US $10–40 billion and many speculated that the company had participated in market manipulation.[xx] Porsche reaffirmed that its move towards acquiring Volkswagen was purely strategic, rather than motivated by financial gains.

In 2009, Porsche and Volkswagen agreed to merge and in December of that year Porsche sold 49.9 per cent of Porsche Zwischenholding GmbH, the holding company for its automotive operations, to Volkswagen.[xxi] An agreement for a complete merger was in place until the end of 2011. However, collecting debt amounting to EUR 10 billion made it difficult for Porsche to gain the support of lenders during the financial crisis.[xxii] Additionally, pending lawsuits against Porsche SE eventually m ade it too arduous to value the company, and the merger agreement was aborted. Porsche stated that “preparations for the merger were terminated, because in the merger negotiations the companies could not agree on the exchange ratio”.[xxiii] Both companies are still willing to continue a collaborate relationship as a stepping stone towards an ‘integrated automotive group’.[xxiv] Moreover, Volkswagen does hold the opportunity to exercise options to buy the remaining stake of Porsche Zwischenholding GmbH between November 2012 and January 2015.[xxv] If Volkswagen does decide to purchase the remaining stake, the automotive operations of Porsche will be integrated into Volkswagen’s.

Volkswagen’s foreign currency exposure

Volkswagen, like Porsche, manages its foreign currency exposure utilizing derivatives such as forwards, options and swaps. However, a major difference lies in Volkswagen’s reliance on developing a natural hedge with 54 international production sites across Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America.[xxvi] Within each location, Volkswagen has been able to adjust its production levels to accommodate fluctuations with currency exchange. The firm has also established larger operations in areas where currency can have a significant impact on its operations. For example, the United States is a substantial market for Volkswagen, so to further reduce currency exposure, the company has established local production facilities and procurement relationships. Given the flexibility of its international production, roughly 50 per cent of Volkswagen’s foreign currency exposure is mitigated through its natural hedging strategy.[xxvii]

If Volkswagen were to purchase the remaining stake in Porsche’s automobile operations, it could affect Porsche’s currency hedging strategy. The brand that signifies ‘made in Germany’ could be fully integrated into Volkswagen’s international production operations. It is unknown how much more and exactly how the two companies will integrate their operations. However, Volkswagen estimates that the move could create savings of around EUR 700 million.[xxviii] Volkswagen’s ultimate goal is to integrate Porsche’s manufacturing and R&D capabilities into its own.

QUESTIONS

- How would you position Porsche’s US operations in Figure 8.1? What is the exposure-absorption capability on the input market side? What are the exchange pass-through capabilities on the output side?

- Compared with other European automakers, what is the magnitude of Porsche’s exposure in the US? Why?

- What is the current exposure management strategy at Porsche?

- Porsche has relied on currency hedging to protect itself. Can Porsche continue to do so in the long run? What would be your strategic answer for currency fluctuations for Porsche in the future?

- What did BMW do to manage its exposure in the US? Can Porsche follow BMW’s approach?

- Could a strengthened relationship between Porsche and Volkswagen affect Porsche’s economic exposure and/or its exposure reduction strategies?

Notes

[i] Michael H. Moffet and Barbara S. Petitt, ‘Porsche exposed’, Thunderbird Case A06–04–0004 (2004), 1–13; ‘Grappling with the strong euro’, The Economist 367 (7 June 2003), 65; David Woodruff, ‘Porsche is back – and then some’, Business Week (15 September 1997),

56; Martin Fackler, ‘Japan makes more cars elsewhere’, New York Times (Late Edition (East Coast)) (1 August 2006), C.1; Porsche company information (2007); Guido Reinking, ‘Porsche will cut costs to cover hedging expiry’, Financial Times (20 October 2004), 26.

[ii] Woodruff, ‘Porsche is back’, 56.

[iii] Fackler, ‘Japan makes more cars elsewhere’, C.1.

[iv] Porsche SE, Annual report (2011), 50–1.

[v] BMW, Annual report (2011), 24–8.

[vi] Mercedes Benz Cars, Annual report (2011), 130.

[vii] The Economist, ‘Grappling with the strong euro’, 65.

[viii] Martha Lagace, ‘Porsche’s risky roll on an SUV’, Harvard Business School (5 September 2006); Porsche SE, Annual report (2011).

[ix] Porsche SE, Annual report (2011).

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Porsche, Annual report (2006).

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Citigroup Smith Barney, Porsche (24 September 2003), 5, cited in Moffet and Petitt, ‘Porsche exposed’, 5.

[xiv] ‘Porsche plans to accelerate China dealership openings this year’, Bloomberg (22 April 2012).

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Reinking, ‘Porsche will cut costs’, 26.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Porsche SE, Annual report (2011).

[xix] Emily Hughes, ‘Fast bucks: how Porsche made billions’, BBC (22 January 2009).

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Christoph Rauwald, ‘Volkswagen calls off Porsche merger’, Wall Street Journal (12 January 2012).

[xxii] Tony Czuczka, ‘Volkswagen clears tax hurdle on Porsche integration WiWo says’, Bloomberg (9 June 2012).

[xxiii] Porsche, Annual report (2011), 12.

[xxiv] Porsche, Annual report (2011), 41.

[xxv] Andreas Cremer and Karin Matussek, ‘Porsche plunges after VW merger fails over pending lawsuits’, Bloomberg Businessweek (9 September 2011).

[xxvi] Porsche, Annual report (2011), 75.

[xxvii] Uta Harnischfeger, ‘VW increases its hedging’, Financial Times (10 September 2003), 29.

[xxviii] Chad Thomas, ‘Volkswagen aims to combine with Porsche as soon as economically “sensible”’, Bloomberg (22 January 2012).