Case 5.2 Organizational transformation at the Tata Group[i]

The Tata Group is an Indian multinational corporation with headquarters in Mumbai, India, and counts 935,000+ employees.[ii] The group has an operational presence in more than 100 countries across six continents. In 2022, it was India’s second-largest conglomerate (after Reliance Industries, active in oil and gas), and the group consisted of 30 companies across ten business sectors. As many as 29 of the Tata enterprises are publicly listed with a combined market capitalization of US $311 billion (2022). Moreover, a significant portion of the group’s total revenue is generated abroad, outside of India, with the United Kingdom and the United States of America accounting for a major share.[iii]

The Tata Group got its name from the firm’s founder, Jamsedji Tata (1839–1904), who established the conglomerate in 1868. Since 1991, Ratan Naval (N.) Tata has acted as the Chairman of the Tata Group and has led the company in its fifth generation of family stewardship. At the end of 2012, Cirus Mistry took over the reins from Ratan N. Tata.[iv] Ratan N. Tata retired in 2012, and Cirus Mistry became the chairman. However, in 2016, Cirus Mistry was dismissed, reportedly due to disagreements with the Tata family regarding business strategy; as a result, Ratan N. Tata came back to manage operations in the interim. Subsequently, in January 2017, Natarajan Chandrasekaran was appointed to the position.

Natarajan Chandrasekaran became the second non-Tata family member to lead the group and embarked on a journey to structurally re-organize the Tata group.[v] The high degree of diversification and internationalization as well as the complex ownership structure in the Tata group create a particular organizational setting, with each product unit commanding unique know-how and management skills.

The history of the Tata Group

In 1902, 44 years after the Tata Group’s foundation, the firm acquired the Indian Hotels Company and built India’s first luxury hotel, the Taj Mahal Palace & Tower. After the death of founder Jamsedji Tata, his son Dorab Tata became the chairman of the Tata Group and further promoted the group’s diversification. Under his management, the group continued to expand its business and entered into a variety of sectors, including steel (1907), electricity (1910), education (1911), consumer goods (1917), and aviation (1932).[vi] In 1907, the group opened its first international representative office in London, UK.

From 1932 to 1938, the first non-Tata chairman in the firm’s history, Nowroji Saklatwala, directed the Tata Group. However, only after the appointment of Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy (J. R. D.) Tata in 1938, the group resumed its diversification strategy and expanded further in industries such as chemicals (1939), technology (1945), cosmetics (1952), marketing, engineering, and manufacturing (1954), tea (1962), and software services (1968). By increasing its scope of business activities, the Tata Group gained worldwide recognition and established its first representative office for North America and Latin America in New York, United States in 1945. In the same year, Tata Engineering and Locomotive Company (in 2003 renamed Tata Motors) was established to manufacture engineering and locomotive products. Later, in 1954, it further expanded to produce commercial vehicles. In 1968, based on internal needs the Tata Group set up Tata Consulting Services, India’s first IT services company, which began to engage in external business in the 1970s. Under J. R. D. Tata’s leadership, the Tata Group grew from only 13 companies in 1938, to 300 in 1991. Most of the subsidiaries and associated companies were managed independently and expanded into a variety of markets. The unstructured strategic development of Tata’s affiliates created an overlap in businesses.

After J. R. D. Tata’s resignation in 1991, the new chairman of the Tata Group, his nephew Ratan N. Tata, conducted an in-depth portfolio analysis of all the Tata businesses in order to increase the group’s competitiveness and to streamline the businesses. In the ensuing restructuring process, Ratan N. Tata segmented the portfolio of businesses into seven industries, namely materials, engineering, energy, consumer goods, chemicals, services and information technology (IT) & communication.

Under Ratan N. Tata’s leadership, the conglomerate accelerated its local and international expansion. For many years, the Tata Group’s international activities focused on exports and the firm’s international expansion was limited mainly to organic growth.[vii] However, over time, the various industry groups broadened their operating platforms and began to source, produce, and sell abroad. In recent years, the Tata Group has revisited further this approach by acquiring a substantial number of well-known companies outside of India. In line with this new internationalization approach, Tata purchased the British brand Tetley Tea in 2000. Today, this wholly owned subsidiary of Tata Consumer Products is the world’s second largest manufacturer and distributor of tea after Unilever. In 2001, the group created the insurance company Tata-AIG, a partnership between the Tata Group and the American International Group (AIG). Three years later, Tata Motors acquired the Daewoo Commercial Vehicle Company, South Korea’s second largest truck producer.[viii] In 2007, Tata Steel expanded its production capacity and merged with the Anglo-Dutch steel manufacturer Corus Group, Europe’s second largest steelmaker. The deal was the largest corporate acquisition by an Indian company ever.[ix] In 2008, Ford and the Tata Motors agreed on the takeover of the two British car manufacturers Jaguar and Land Rover. In the same year, Tata Motors unveiled the Tata Nano, supposedly the world’s cheapest car, which went on sale in 2009.

In June 2018, the Tata Group finalized a deal to merge its steelmaking operations with ThyssenKrupp, a German steelmaker, creating Europe’s second-largest steel company.[x] Other major companies belonging to the Tata Group are Tata Chemicals, Titan, Tata Capital, Tata Power, Tata Advanced Systems, and Tata Communications.[xi]

Managing the business

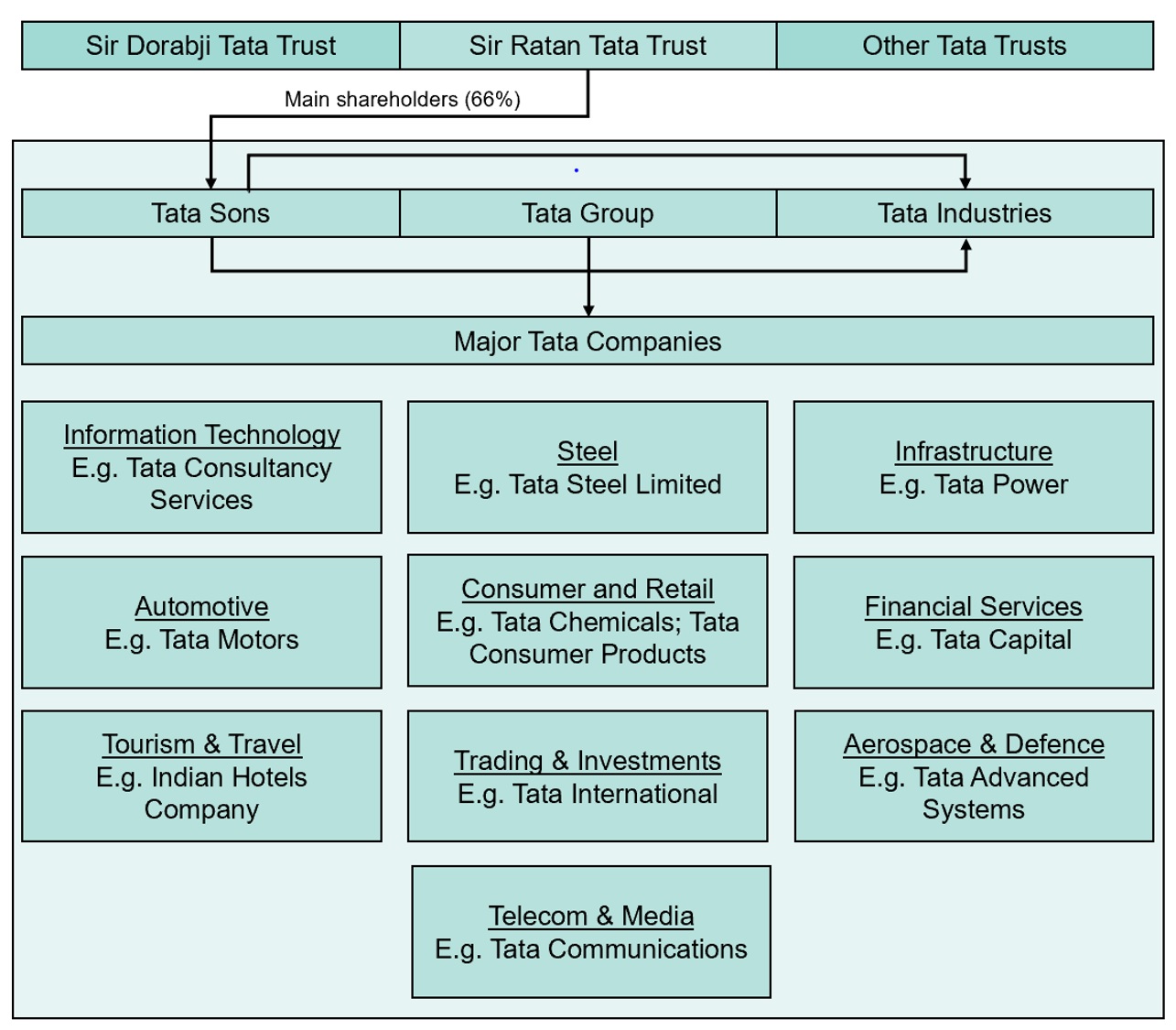

Based on the historical background of the Tata Group, each operating company is responsible for its own international strategy forming “an integral part of its overall strategy, depending on the nature of the industry, opportunities available and competitive dynamics of the global stage”.[xii] The hierarchical functioning of companies within the Tata Group is driven by the ownership structure: “public philanthropic trusts endowed by the members of the Tata family” control the Tata Group.[xiii] These trusts hold 66 per cent of the equity capital of Tata Sons Private Limited (Tata Sons), the principal investment holding company and promoter for the Group companies.[xiv] The two largest trusts are the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust & Allied Trusts and the Sir Ratan Tata Trust & Allied Trusts, which were both established from the estates of the founder of Tata Group.

In 1945, Tata Sons established Tata Industries serving as a managing entity for companies governed by Tata Sons. However, upon removing the management activities from Tata Industries, Tata Sons decided to make Tata Industries responsible for the group’s expansion into emerging and high-tech businesses in the 1980s. Over time, the Tata Industries unit has become an independent entity with its own board of directors and is, next to Tata Sons, the second key holding company of the Tata Group. Today, Tata Industries “promotes and incubates the Tata Group’s entry into new businesses” through its Tata Strategic Management Group and Tata iQ divisions. It has promoted ventures in several sectors: control systems, information technology, financial services, auto components, aerospace and defense, as well as telecom hardware and telecommunication services.[xv] Further, Tata Industries invests in Tata’s operating affiliates to enhance growth and it secures control throughout the Tata Group by keeping at least a minority stake in a wide range of Tata companies.

The principal holding company’s relationship with the companies in the Tata Group is governed by its shareholding in the companies, as well as its Brand Equity & Business Promotion (BEBP) agreement. According to the BEBP agreement, the operating companies must adopt the Tata Code of Conduct (TCoC) and the Tata Business Excellence Model (TBEM). Given that each company is managed as a stand-alone entity, Tata Group created the Group Corporate Center as Tata’s main decision-making body. It reviews the growth of individual firms and assesses possible further market entries and product diversification. Under Chairman Ratan N. Tata, this body has also provided guidance in terms of financial, legal, human resources and other operational policies, and it analyses the portfolio of the Tata Group across industries.

The rapid expansion under J. R. D. Tata’s leadership was associated with a lack of corporate identity. In order to gain more control over its many affiliates and an improved ability to influence their operations, Chairman Ratan N. Tata increased Tata Sons’ equity stake in all Tata companies from small minority stakes to a minimum of 26 per cent, thereby allowing (a) Tata Sons to exercise a veto right against potential takeovers and (b) the Group Corporate Center to oversee actively all business operations.[xvi] In the past, affiliates had automatic permission to use the Tata brand without compensating the group. However, Tata Sons owns the name ‘Tata’ as well as the Tata trademarks, and therefore has the right to authorize their use by Tata companies for their products and services. In the 1990s, Ratan N. Tata changed Tata’s brand management so that all operating companies that make use of the Tata brand and trademarks have to pay a licensing fee.[xvii]

Figure 5.8 illustrates the holding structure of the Tata Group. The shaded region represents the Tata Group. All companies belonging to the Tata Group are under management of the Group Corporate Center and are supported by the holding companies Tata Sons and Tata Industries. The philanthropic trusts own 66 per cent of equity of Tata Sons, which in turn, jointly with Tata Industries, is a major shareholder in all Tata companies: e.g., Tata Sons has around 72 per cent in shares of Tata Consultancy Services [xviii]; Tata Sons and Tata Industries hold around 30 per cent and 2 per cent respectively of Tata Motors’ equity[xix] and Tata Sons owns around 29 per cent of Tata Steel’s stocks.[xx]

Tata Consultancy Services

As the key unit that has been characterized by rapid international expansion, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) was established in 1968 as the result of internal demand for information related systems. In contrast to most other operating companies of the Tata Group, TCS is a relatively young company in a fast-moving industry that rapidly expanded internationally and did not only rely on the domestic and export markets.

It was really twenty senior managers from various Tata companies who combined their forces to provide consulting services to Tata’s businesses. Based on the increasing complexity of requests, TCS quickly expanded its consultancy business into information systems development (e.g., automation of the payroll and financial systems at Tata companies) and data services (e.g., data processing). Until 1990s, TCS had only limited competition in India, since its only rival, namely IBM, decided to exit the Indian market due to the 1977 regulations limiting foreign investors to a minority stake in Indian firms.

As the result of an agreement to become the exclusive marketing agent in India for Burroughs, a former leading US business equipment manufacturer that later merged with Sperry and resulted in Unisys, TCS would enter the US market in 1974 by exporting software services to the Detroit Police. In 1978, TCS refused an offer from Burroughs jointly to manufacture computers through a joint venture arrangement in India. Instead, TCS decided to focus on its own competences. Former Chief Executive Officer and later Vice Chairman of TCS, Mr. Subramaniam Ramadorai, explained: “When we gave up Burroughs, the pressure was on to build the business. Our strength was our line-of-business experience, our ability to learn quickly, and our confidence.”[xxi]

As a result, in 1979, TCS’ management established its first international representative office in New York, United States. From then on, TCS would not only build up its position in the US market, but, as its IT projects were related to a variety of new technologies, TCS would also gain access to the latest know-how across a variety of industries and rapidly enrich its employees’ skills. After finishing a client’s project, consultants were sent to India to share the acquired knowledge of new technologies with their colleagues and teach them. TCS called this process ‘bootstrapping’.

With the introduction of software migration combining “an existing application that had 90 per cent of the functionality that the enterprise needed, and add[ing] the other 10 per cent after migration”, TCS created a new, cost-efficient and less risky solution approach for US and European enterprises that had to upgrade their computer systems and transfer existing software from old to new servers.[xxii] After the first international migration project at a US bank consortium, TCS would further expand its international business, and its migration services quickly turned into a major source of TCS’ international revenue.

In the late 1980s, the demand for domestic and international assignments began to change. While Indian companies asked for the automation of operations, software development and packaged application services, international clients demanded implementation of systems embodying the latest technologies and providing them a strategy edge. Despite the more promising outlook for revenues from abroad, TCS continued its activities on the domestic market. This strategy proved to be effective as local operations would regularly develop software packages that could then later be applied in international projects (e.g., the communications software ‘C-Dot’ was first introduced in the Indian market, but later used in communication projects abroad).

Driven by its domestic and especially its international successes, TCS aimed to strengthen its global footprint. With the Global Network Delivery Model allowing TCS “to seamlessly and uniformly deliver services to global customers from multiple global locations in India, China, Europe, North America and Latin America”, TCS was able to establish global service standards.[xxiii] In 2002, TCS established a global delivery centre in Uruguay, which became “one of the largest outsourcing operations in Latin America”.[xxiv] This centre has a leading role in TCS’ operations in Latin America and interacts with global delivery centres in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador and Peru. TCS’ investment decision to enter Uruguay resulted from generous government intervention: the TCS’ affiliate was established in a new upscale technology park in a free trade zone, allowing operations at reasonable costs. Further, Uruguay offered strong government support in favour of the IT industry, a stable political and economic environment and highly skilled graduates.[xxv] Together with the TCS IT centres in Columbia and Argentina, Uruguay formed a cluster streamlining “internal processes, resulting in a synergy among the three companies that led to more efficient services of better quality”.[xxvi] In 2012, TCS operated three Uruguayan facilities specializing in business process outsourcing, IT project implementation and advanced IT services and offering its assistance to clients in the Americas and beyond. The implementation of the global network delivery model created a competitive advantage. TCS was now able to send consultants to different parts of the world and could guarantee a structured business approach controlled by the head office and implemented in a disciplined fashion.

The above modus operandi, however, created organizational challenges, as employees were constantly working on projects with changing geographic scopes: an average of 48 per cent of TCS’ revenues was generated from projects conducted at client locations, 46 per cent was created at delivery centres in India (though much of this for foreign clients), and 6 per cent came from global delivery centre in 2014.[xxvii]

After 30 years of domestic and international organic growth, TCS made its first strategic purchase in 2001 when acquiring CMC (Computer Maintenance Corporation), an IT services, consulting and software provider, from New Delhi, India. In 2004, TCS bought three further Indian IT companies, namely Airline Financial Support Services India, Aviation Software Development Consultancy India, and Phoenix Global Solutions. In 2005, TCS completed its first international takeover with Sydney-based Financial Network Services. Thanks to this buyout, TCS gained knowledge about IT solutions and services at international financial institutions, secured access to a valuable global customer base and strengthened its position in the profitable banking, financial services and insurance sector.

In the same year, TCS and Pearl, a UK insurance company, agreed to a ‘structured deal’ that created a new subsidiary with TCS as the majority stakeholder. A further expansion in the financial services industry was the acquisition of Comicrom in late 2005. The Chile-based business process outsourcing company was focused on the banking and telecommunication sector, but was not capable of providing one-stop-shopping IT solutions. Here, combining resources from TCS’ global delivery centers in Latin America and Comicrom created a powerful platform to serve this market.

In 2006, TCS absorbed Tata Infotech, a second IT company of the Tata Group, in order to create synergies and opportunities for cross-selling. Tata Infotech was specialized in the telecommunications and defence sectors and complemented TCS’ capabilities in these areas. Still another acquisition was completed in 2008 when TCS acquired Citigroup’s India-based Citigroup Global Services, a business processing outsourcing company. Chief operating officer and executive director Natarajan Chandrasekaran outlined the synergies as follows: “This acquisition gives us the ability to offer an end-to-end, domain-led third-party solution for business operations to our large financial services clients. We will also work to create platforms for the future and integrate our strong domain expertise in operations along with our suite of products for the financial services sector.”[xxviii]

As of June 30, 2021, TCS operates in 46 countries, representing 155 nationalities.[xxix] For the fiscal year ending March 31, 2021, TCS derived 94 per cent of its US $19 billion in revenues from abroad, mainly from the Americas and Europe with 51 per cent and 32 per cent respectively.[xxx] With a headcount of 509,000+ employees, TCS has deep domain expertise in multiple industry verticals, which are often referred to as industry service units (ISUs). The five ISUs are: (1) banking, financial services and insurance, (2) retail and consumer business, (3) communications, media and technology, (4) manufacturing and others, (5) life sciences and healthcare, energy, resources and utilities, public services and others. TCS uses these “verticalized, customer-centric organization structure to foster domain and contextual knowledge within the ISUs”.[xxxi] Geographically, TCS operates in North America, Latin America, the United Kingdom, Continental Europe, Asia-Pacific, India, Middle East and Africa. Moreover, TCS obtains more than one-fifth of its revenue from emerging markets such as from India, Middle East, Africa, and Asia-Pacific.[xxxii]

In March 2021, TCS released a new brand statement, ‘Building on Belief’. It represents a brand promise based on the core strengths that TCS has come to be known for. These include: a long-term approach based on shared purpose that benefits clients through the breadth of reach and ubiquity of involvement; innovation and the responsible, sustainable and strategic view it provides; and the ability to harness collective knowledge to create technology-led solutions for transformative, measurable impact.” Through this new brand statement, CEO and Managing Director of TCS, Rajesh Gopinathan, stated it would “pave the way to engage with [TCS’s] customers as their growth and transformation partners and bring together our contextual knowledge and expertise to help them master their journey.”[xxxiii]

Corporate social responsibility at the Tata Group

As early as in 1912, the Tata Group integrated corporate social responsibility (CSR) in its working environment and implemented an eight-hour workday for employees, possibly being the first company worldwide to do so. In addition, in 1917, the Indian firm started to provide medical services and promoted, along with some other leading pioneers, the introduction of further social advantages for its employees such as pension funds, maternity aids and profit-sharing programmes.

Tata Sons receives around 66 per cent of Tata Group’s profits. As an additional financial support, the trusts receive 4 per cent of the operating income of each company belonging to the Tata Group and every generation of the Tata family passes a large share of its inheritance on to the trusts. In addition to its function as a holding company, the main objective of Tata Sons is to improve social well being. This philanthropic approach helps to support a vast array of projects, to fund new initiatives and to finance charities in the areas of quality research, education and culture. Some of the organizations that have been established include the Tata Institute of Social Sciences offering undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in social work (e.g., rural development, health administration), the Tata Memorial Hospital specializing in cancer treatments and research, and the National Centre for the Performing Arts focusing on the performing and allied arts (e.g., it is the home of the Symphony Orchestra of India).

In addition to Tata’s commitment to local philanthropy, the conglomerate is also actively engaged in international CSR initiatives. In 2010, Chairman Ratan N. Tata decided to donate US $50 million to the Harvard Business School (HBS), the largest international donation in the school’s history.[xxxiv] This gift was supposed to fund a new academic and residential building, the Tata Hall, for the executive education programs on campus in Boston, United States. Previously (in 1975), Ratan N. Tata attended one of the HBS advanced leadership programs and in 1995, he was honoured with the HBS’s highest distinction, the Alumni Achievement Award.[xxxv]

A more dramatic event led to the Tata Swach project, meaning ‘clean’ in Hindi. After the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean, thousands of people lost their homes and did not have access to clean drinking water. Five Tata companies, namely Tata Chemicals, TCS, Titan, Tata Autocomp Systems and Tata Business Support Service joined forces and developed a compact, nanotechnology water purification device for use at home. With a capacity of 3 to 4 litres per hour, this water purifier enables families to filter their own drinking water as it removes “the minutest visible impurities in water”.[xxxvi] The filters purify around 3,000 litres and hence last about one year for a family of five people. The device costs around US $21 and is therefore an affordable solution for families with no access to clean drinking water in their environment. A major plus of the Tata Swach is the fact that it does not rely on the use of electricity. Thanks to the product, Tata has helped to decrease the risk of infection of cholera, diarrhoea and other diseases. Mr Ashvini Hiran, former Chief Operating Officer Consumer Products Business of Tata Chemicals, explained the driving forces behind this project: “Safe drinking water is a basic human right and Tata Swach combines technology, performance, design and convenience to serve this basic human right of millions of consumers. The company has made affordability an important part of its innovation efforts.”[xxxvii] At present, the water purifier belongs to the product portfolio of Tata Chemicals. After focusing solely on the Indian market for a long time, Tata Chemicals studied the African continent for international sales of the Tata Swach. Additional enquiries from South America, China, South East Asia, etc. poured in and further stimulated Tata Chemicals’ international activities. As Mr Sabaleel Nandy, former head of the water purifier business at Tata Chemicals, explained: “International expansion needs to be carefully thought through. We will have to evolve an international model. We need to ramp up production considerably or set up a factory abroad.”[xxxviii] As one example of the outcomes thereof, in 2021 a total 11,770 households gained access to clean water through the Swach Project. “Rural sanitation was improved through [the] behaviour change programme, Swachh Bharat Mission Cleanliness Drives and construction of toilets and sanitation units.”[xxxix]

In addition, Tata Chemicals focuses on the business of LIFE – Living, Industrial and Farm Essentials. By covering niche markets and strongly investing in R&D capabilities, Tata Chemicals is attempting to strengthen its market position and to advance its knowledge in the emerging fields of nanotechnology and biotechnology.[xl] Through a joint venture with Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory from Singapore, Tata Chemicals is trying to develop a special type of seedlings to produce bio fuel in India and at a later stage in other parts of the world.

Overall, most Tata companies invest heavily in R&D in local and international subsidiaries, as well as in strategic partnerships and joint ventures and promote sustainable solutions in a wide range of industries. A further example is the UK division of Tata Steel Research, Development and Technology that is involved in electrical steel making. Although modern electric arc furnaces at Tata Steel make use of recycled steel scrap, steel manufacturing has negative environmental effects to consider (e.g., from the use of cooling water, electricity generation, air released from production processes etc.). Therefore, the main focus of the research projects in Tata Steel’s UK subsidiary in Port Talbot, is to design a more sustainable approach to steel making and to reduce related environmental harms.

Currently, there are ten core principles that the Tata companies are committed to, so as to create a positive societal impact and effective initiatives. Examples of such principles are beyond compliance, impactful, and relevant to national and local contexts.[xli] Along with Tata trusts, Tata has established the Tata Sustainability Group which “serves as the nodal resource on sustainability for Tata group of companies”. Tata Sustainability Group also set up Tata Engage to encourage volunteering across the Group. Many Tata colleagues, family members and retired Tata employees are associated with the initiative today.[xlii]

False belief?

When studying Tata Group’s CSR engagement, the image projected towards the outside world is that of one of the most visionary emerging multinational enterprises in the world. Tata companies pride themselves on avoiding ‘dubious’ businesses and of relying on honest deals. As former Chairman Ratan N. Tatan explained: “You really have to take a view that you are above what, in the Indian context, is considered normal. If I had to pay a bribe to enter a particular business, I just wouldn’t be able to live with myself. Today, the greatest strength we have is that we are known to be people who don’t play dirty and rationalize our ethical lapses.”[xliii]

However, Tata’s history does include a number of less inspiring episodes. In the 1860s, Tata Group founder Jamsedji Tata established a private trading firm. He and his brother were opium traffickers and exchanged opium for tea, silks and pearls from China. The profits generated by Jamsedji Tata’s family from the opium trade built the major share of the seed capital with which the Tata Group built several cotton mills in the province of Bengal, a leading producer of opium.

Figure 5.8

The Tata Group holding structure

With the launch of the Empress Mills in Nagpur, the Tatas began to prosper and as a result the Tata business empire could flourish.[xliv] This may appear somewhat at odds with founder Jamsedji Tata stating: “We do not claim to be more unselfish, more generous or more philanthropic than other people. But we think we started on sound and straightforward business principles, considering the interests of the shareholders our own, and the health and welfare of the employees, the sure foundation of our success.”[xlv]

Despite the fact that opium trade was legal at that time in history, it somewhat contradicts the core values of the Tata Group, being integrity, understanding, excellence, unity and responsibility. After some negative publicity about the personal use of company funds among senior managers in the 1990s, Ratan N. Tata promoted the implementation of a written Code of Conduct. Today, this Code of Conduct that is regularly updated “serves as the ethical road map for Tata employees and companies”.[xlvi]

QUESTIONS

- What was the Tata Group’s initial organizational approach at the beginning of the nineteenth century and did this approach change over time (centralized exporter, international projector, international coordinator or multicentred MNE)? Please justify your answer.

- How does the Tata Group manage its internal network, taking into account Bartlett and Ghoshal’s views about multinational networks?

- Has the Tata Group been able to transfer knowledge from “strategic leader” affiliates to other affiliates? Please identify an example in the case.

- Especially in the context of doing business in India and other emerging economies, applying ethical principles such as avoiding shady deals without foregoing business opportunities, is easier said than done. What reasonable preventive measures can limit such business risk? How can these precautions be integrated in the organizational functioning of the Tata Group? In general, do you think that the group’s past plays a role in its present approach to CSR?

Notes

[i] This case was co-authored by Ms Jenny Hillemann, Ms Jasmeen Gill and Professor Alain Verbeke.

[ii] Tata Group company information, 2021.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Deccan Herald, Four years of N Chandrasekaran as Tata Sons chief: How he changed the course of the conglomerate (21 February 2021).

[vi] Tata Group, Company brochure 2012 (March 2012).

[vii] Tarun Khanna, Krishna G. Palepu and Richard J. Bullock, ‘House of Tata: Acquiring a global footprint’, Harvard Business School (2009), Case: 9–708–446.

[viii] Sanjay Singh, Meera Harish and Kulwant Singh, ‘Tata Motors’ integration of Daewoo Commercial Vehicle Company’, Richard Ivey School of Business (4 December 2008)

[ix] Tata Group, Company brochure 2012 (March 2012).

[x] Nolen, J. L.. “Tata Group.” Encyclopedia Britannica (4 September 2018). https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tata-Group.

[xi] Tata Group company information, 2021.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Tata Group, Company brochure 2012 (March 2012).

[xiv] Wee Beng Geok and Ivy Buche, ‘Tata Consultancy Services: A systems approach to human resource development’, Nanyang Business School (30 March 2012)

[xv] Tata Group company information, 2021.

https://www.tata.com/business/tata-industries

[xvi] Tarun Khanna, Krishna G. Palepu and Richard J. Bullock, ‘House of Tata: Acquiring a global footprint’.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Tata Consultancy Services, Annual report FY 2020-2021, 2021.

[xix] Tata Motors, Annual report FY 2019-2020, 2020.

[xx] Tata Steel, Annual report FY 2020-2021, 2021.

[xxi] Gary C. Mekikian and John D. Roberts, ‘Tata Consultancy Services: Globalization of IT Services’, Stanford Graduate School of Business (2009), Case: IB-79.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Pankay Ghemawat and Steven Altman, ‘Tata Consultancy Services: Selling certainty’,

Harvard Business Review 2011, Case: PG0–004.

[xxv] Tata Consultancy Services company information, 2012.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Tata Consultancy Services, Annual report FY 2011–2012, 2012.

[xxviii] Tata Consultancy Services company information 2008.

[xxix] Tata Consultancy Services company information 2021.

[xxx] Tata Consultancy Services, Annual report FY 2020-2021, 2021.

[xxxi] Tata Consultancy Services, Annual report FY 2020-2021, 2021.

[xxxii] Tata Consultancy Services company information 2021.

https://www.tcs.com/investor-relations#section_6

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] Harvard Business School, Harvard Business School receives $50 million gift from the Tata Trusts and Companies (14 October 2010).

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Tata Swach company information, 2012.

[xxxvii] Tata Group company information, 2012.

[xxxviii] Tata Group company information, 2011.

[xxxix] Tata Chemicals Annual report FY 2020-2021, 2021.

[xl] Tata Swach company information, 2012.

[xli] Tata Sustainability Group, CSR (4 August 2021) https://www.tatasustainability.com/SocialAndHumanCapital/CSR

[xlii] Tata Sustainability Group company information, 2021.

[xliii] Rohit Deshpande, ‘Tata Consultancy Services’, Harvard Business School (3 November 2009).

[xliv] Mary L. Kienholz, Opium Traders and their worlds – Volume Two (2008), iUniverse, Bloomington, Indiana.

[xlv] Tata Group company information, 2008.

[xlvi] Tata Group company information, 2012.